VESTIR-SE DE RAÍZES PARA VOAR

Uma constatação simples pode alterar nossa maneira de olhar para o mundo: todos nós estivemos no ventre de nossa avó materna, já que bebês biologicamente do sexo feminino desenvolvem durante sua gestação todos os óvulos que a acompanharão vida afora, inclusive aquele que nos gerou. Algo das alegrias, medos, energias, dúvidas e esperanças de nossas avós foi-nos transmitido enquanto parte de nós formava-se em nossa mãe-feto e não apenas na presença das mães de nossas mães em nossas vidas, seja de forma física ou a partir dos relatos que herdamos. Esse corpo-avó é, portanto, um território de criação, polinização, coletividade e de conexão entre gerações, tempos e lutas. Reconhecer e honrar esse vínculo pode romper com a lógica que o mundo moderno ocidental nos legou, com seu individualismo, competição e exclusão, isolando e invisibilizando muitas vezes as pessoas velhas em prol de uma celebração exacerbada da juventude e do futuro.

Foi justamente quando o futuro foi suspenso, com a pandemia de COVID-19 e toda a crise desencadeada a partir daí, que o conjunto de obras apresentadas nesta exposição foi criado. Em meio a questionamentos sobre sobrevivência, confinamentos, pulsão de vida, incertezas e as transformações necessárias para a invenção de um novo mundo, Roberta Goldfarb mergulhou ainda mais fundo em sua ancestralidade para vislumbrar o porvir. Sua pesquisa em geral versa sobre uma espécie de taxonomia dos afetos e traz reflexões sobre a condição das mulheres e a maternidade e com esta nova safra amplifica-se para uma discussão sobre matrilinearidade, ecofeminismo e migrações. O corpo da artista é árvore que alimenta seus filhos enquanto é alimentado por suas raízes, numa sobreposição de sutis camadas de imagens feitas por ela em quase uma década. Ao lado dessa grande instalação estão ninhos que acolhem a fusão das batidas do coração coletadas em todas as ultrassonografias feitas em suas gestações com o tambor usado em suas rodas de mulheres.

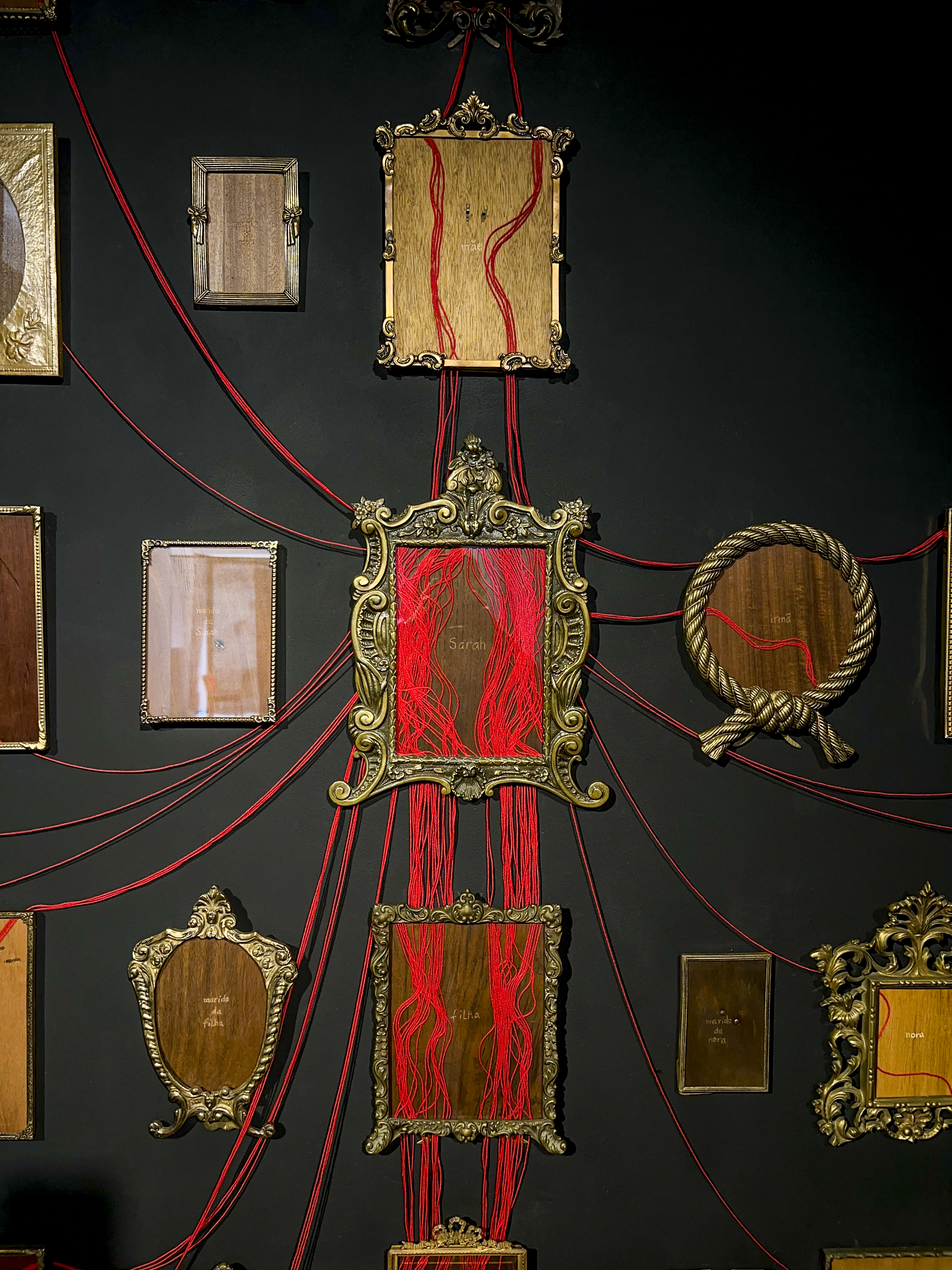

Ao revisitar o episódio do anjo da morte que ceifou a vida de todos os primogênitos na passagem bíblica das 10 pragas do Egito, a artista personifica o anjo da vida. Novamente o tecido entra em cena, trazendo sutileza para os gestos executados como anjo, pássaro ou borboleta. Na natureza os pássaros migram em busca de condições de sobrevivência, assim como boa parte dos humanos. No vídeo Wie Nemt Men a Bissale Mazel (Onde conseguir um pouco de sorte) vemos resquícios da trajetória migratória da Polônia para o Brasil feita por Nechuma (Sarah), avó materna de Roberta, em palavras retiradas de documentos encontrados numa extensa pesquisa feita pela artista e carimbadas num papel. Carimbos muitas vezes decidem destinos, quem vive e quem morre, quem tem direito ou não de mudar de país. A migração da avó foi o que deu a Roberta o passaporte para permanecer na Europa e fez emergir essa nova perspectiva sobre sua própria história. Iniciamos a exposição com uma árvore-corpo (descendente) e finalizamos com uma árvore-útero (ascendente/descendente). Toda a humanidade esteve dentro do ventre da mulher é uma árvore genealógica centrada em Sarah, mas ressaltando a presença de todas as mulheres entrelaçadas em sua vida: mãe, avó, irmãs, cunhadas, cocunhadas, filhas, netas, bisnetas... Há tempos discutimos os males e as consequências do patriarcado para os seres da Terra e sonhamos e tentamos construir uma transformação em que outros valores sejam nossos guias. Seria a virada para o matriarcado a solução que precisamos? O certo é que sem compreendermos o passado não temos futuros, sem honrar as mulheres não há transformação, sem reconhecer nossa interdependência com os demais seres do planeta não há salvação. Como Roberta Goldfarb nos faz refletir precisamos vestir-nos de raízes para podermos voar.

Cristiana Tejo

Curadora

Nowhere - Lisboa

DRESS UP IN ROOTS TO FLY

A simple observation can change our way of looking at the world: we were all in the womb of our maternal grandmother. Female babies develop all the eggs that will accompany them throughout their lives during their gestation, including the one that generated us. Something of the joys, fears, energies, doubts and hopes of our grandmothers were transmitted to us as part of us was being formed in our mother-fetus and not just in the presence of our mothers' mothers in our lives, whether physically or from the stories we inherited. This grandmother-body is, therefore, a territory ofcreation, pollination, collectivity and connection between generations, times and struggles. Recognizing and honoring this bond can break with thelogic that the modern western world has bequeathed us, with its individualism, competition and exclusion, and in isolating and making old people often invisible in favor of an exacerbated celebration of youth and the future.

It was precisely when the future was suspended,with the COVID-19 pandemic and the entire crisis unleashed from there, that the set of works presented in this exhibition was created. In the midst of questions about survival, confinement, the pulse of life, uncertainties and the transformations necessary for the invention of a new world, Roberta Goldfarb delved even deeper into her ancestry to glimpse the future. Her research, in general, dealswith a kind of taxonomy of affections and brings reflections on the condition of women and motherhood, and with this new crop it expands into a discussion on matrilineality, ecofeminism, and migrations. The artist's body is a tree that feeds its children while being fed by its roots, in an overlap of subtle layers of images made by her in almost a decade. Next to this large installation are nests that host the fusion of the heartbeats collected in all the ultrasounds performed in their pregnancies with the drum used in their women's cycles.

By revisiting the episode of the angel of death that took the lives of all the firstborn in the biblical passage of the 1o plagues of Egypt, the artist personifies the angel of life. Once again, the fabric enters the scene, bringing subtlety to the gestures performed as an angel, bird or butterfly. In nature, birds migrate in search of survival conditions, as well as most humans. In the video Wie Nemt Men a Bissale Mazel (Where toGet a Little Luck) we see remnants of the migratory trajectory from Poland to Brazil made by Sarah (Sura), Roberta's maternal grandmother, in wordstaken from documents found in an extensive research carried out by the artist and stamped on paper. Stamps often decide fates, who lives and who dies, who has the right or not to move to another country. Her grandmother's migration was what gave Roberta the passport to stay in Europe and gave rise to this new perspective on her own history. We started the exhibition with a tree-body (descending) and ended with a tree-womb (ascending/descending). All of humanity was inside the woman's womb is a family tree centered on Sarah, but emphasizing the presence of all the women intertwined in her life: mother, grandmother, sisters, sisters-in-law, daughters, granddaughters, great-granddaughters... we discuss the evilsand consequences of patriarchy for Earth beings and we dream and try to build a transformation in which other values are our guides. Is the turn to matriarchy the solution we heed? What is certain is that without understanding the past we have no future, without honoring women there is no transformation, without recognizing our interdependence with other beings on the planet there is no salvation. As Roberta Goldfarb makes us reflect, we need to dress up as roots so we can fly.

Cristiana Tejo

Curator

Nowhere - Lisbon